civil war

Happy New Year! (Part 1)

This illustration of New Years Day by Thomas Nast compares and contrasts the state of affairs in the North and the South during the Civil War year of 1864.

The left of the pictures presents scenes of happiness and joy in the North. Union Soldiers are on furlough, celebrating the new year with their family. A small inset image shows former slaves celebrating their recent emancipation. Children are seen happy and playing. A picture of a union soldier shows him to be well fed, clothed and equipped.

In contrast, the images on the right show the sad state of affairs in the South at this time. A woman and several children are shown weeping and grieving over a fresh grave . . . presumably that of the woman’s husband, and the father of the children. A rebel soldier is seen in a tattered uniform, unable to protect himself from the bitter cold.

The upper inset image implies a spiritual component to the Civil War, with scenes of heavenly and demonic beings pitted against one another.

Image and description courtesy of Son of the South – http://www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/civil-war/1864/january/new-years-day.htm

Services Performed by the Invalid Corps – 4th Regiment

These posts are part of a larger series highlighting the contributions and accomplishments of the Invalid Corps/Veteran Reserve Corps during the Civil War. This post only captures some of the activities of individual regiments. Clearly, this is an area ripe for additional research.

4th Regiment

Organized at Rock Island, Ill., October 10, 1863, by consolidation of the 128th, 129th, 135th, 136th, 137th, 138th, 140th, 141st, 153rd and 166th Companies, 1st Battalion. Mustered out July 17, 1865, to January 23, 1866, by detachments.

Principally at Rock Island Barracks and Camp Butler, Ill., guarding rebel prisoners, escorting exchanged men to the front, and performing ordinary guard duty of camps and public stores. Prisoners escorted to different points for exchange, 3,825; escapes, 2.

Services Performed by the Invalid Corps – 3rd Regiment

These posts are part of a larger series highlighting the contributions and accomplishments of the Invalid Corps/Veteran Reserve Corps during the Civil War. This post only captures some of the activities of individual regiments. Clearly, this is an area ripe for additional research.

3rd Regiment

Organized October 10, 1863, by consolidation of the 8th, 10th, 16th, 28th, 50th, 54th, 168th, 172nd, 189th and 190th Companies, 1st Battalion. Mustered out by Detachments June 28 to December 15, 1865.

During part of the year has been stationed at Washington, performing the ordinary duties of the garrison of Washington, of course in conjunction with other troops. While at the Soldiers’ Rest an immense number of troops, from 800 to 6,000 -per day, passed through to the front. At Alexandria, Va., an average of 600 per day forwarded. At Eastern Branch corral many thousand of Government cattle guarded without loss. Regiment on duty at seventy-five points and in six States at one time. The detachment at New Haven escorted 2,280 men to the front, and (aided by other troops) guarded 6,000 men during the process of organization; duty for six months averaged eight hours per day for each man. One detachment assisted by a company of the Pennsylvania Bucktails, took charge of the One hundred and ninety-third Regiment New York Volunteers, at that time 200 strong, over 400 having deserted; in about two months the regiment was sent off with 1,022 men. At Burlington, Vt., a violent outbreak in a volunteer brigade was quelled by seventy men of the Third, two of the rioters being shot, some ironed, and many arrested. Duty of regiment severe; for weeks together on guard every other day; men known to fall asleep with exhaustion while walking their beats. Discipline excellent, notwithstanding that 608 men were received and 863 discharged, &c., during the year.

Reference:

The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies – https://archive.org/details/warrebellionaco17offigoog/page/n574

Services Performed by the Invalid Corps – 2nd Regiment

These posts are part of a larger series highlighting the contributions and accomplishments of the Invalid Corps/Veteran Reserve Corps during the Civil War. This post only captures some of the activities of individual regiments. Clearly, this is an area ripe for additional research.

2nd Regiment

Organized at Detroit, Mich., October 10, 1863, by consolidation of the 38th, 52nd, 101st, 106th, 110th, 111th, 240th, 242nd and 247th Companies, 1st Battalion, and 6th Company, 2nd Battalion. Mustered out by detachments from July 3 to November 11, 1865.

Headquarters at Detroit, Mich., detached companies at various points throughout the North; patrol, escort, and ordinary guard duty. From headquarters the following men have been conducted to the front: Recruits, 1,026; substitutes, 202; conscripts, 140; convalescents, 805; stragglers, 201; deserters, 242; paroled prisoners, 242; total, 2,858; escapes, 16. Similar service was performed by the detached companies, but no numerical records forwarded to this Bureau.

Reference:

The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies – https://archive.org/details/warrebellionaco17offigoog/page/n574

Services Performed by the Invalid Corps – 1st Regiment

One of the smaller things I wanted to do with this project was to increase the visibility of at least some of the activities of the Invalid Corps (Veteran Reserve Corps). One of the most common questions or comments from people is that they mention an ancestor in one regiment or another and ask about what may have been their duties. That, coupled with a desire to understand more fully the contributions of the Invalid Corps to the Civil War (beyond the Battle of Fort Stevens) resulted in this series.

Thankfully, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies, includes a “final report” to Brigadier General James Fry, Provost Marshal General from J.W. De Forest, Captain, Veteran Reserve Corps and Acting Assistant Adjutant-General on November 30, 1865. In it, he breaks down some of the services performed by the various Invalid Corps (Veteran Reserve Corps) regiments. Specifically, the 1st Battalion. By this point in time, the 1st Battalion soldiers were under the authority of the Provost Marshal’s Office and the 2nd Battalion soldiers (those with more significant injuries and illnesses) were under the authority of the Surgeon General of the Army.

These posts only capture some of the accomplishments of individual Invalid Corps/Veteran Reserve Corps regiments. Clearly, this is an area ripe for additional research.

1st Regiment

Organized at Washington, D.C., October 10, 1863, by consolidation of the 17th, 34th, 97th, 103rd, 113th, 114th, 142nd, 144th, 145th and 151st Companies, 1st Battalion. Mustered out by detachments from June 25 to November 25, 1865.

At Elmira, N. Y., performing patrol duty and guarding hospitals, store-houses, and camp of rebel prisoners. Up to the close of the war the prisoners constantly in camp averaged between 10,000 and 12,000; frequent attempts to escape and one prisoner recorded as escaped; duty of guarding them very severe.

Squads of convalescents, recruits, conscripts, &c., generally 80 or 100 strong, escorted to the front or to other posts; no record of a single escape. Many volunteer troops disbanded at this station; at one time 16,000 present; various disturbances resulted; order restored by this regiment. Two companies on duty at Rochester, N. Y., repressing disorders committed by disbanding regiments.

Reference:

The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies – https://archive.org/details/warrebellionaco17offigoog/page/n574

The Power of the Minié Bullet

In this documentary about the Invalid Corps, one of the things that has come up over and over are the devastating injuries received by the soldiers and the significant loss of life.

Looking at the numbers, an estimated 620,000 men died. That breaks down to about 2% of the population. One in four men who went to war, never came home. There’s likely not a family, nor a household that went untouched by the war. More than 476,000 soldiers were wounded leading to almost 40,000 amputations.

One of the reasons for this was the 1849 invention of the Minié bullet, or as Americans called it, the “minie ball”. Rather than the round ball-shaped bullets of the past, the minie ball was a .58 caliber conical bullet made of soft lead with, three ridges in the side, and a hollow base. It weighed about 1 oz. and had a 1/2 inch circumference.

In the 1850s, James Burton, a master armorer at the U.S. Arsenal in Harpers Ferry improved on Minié’s design. He made the bullet longer, thinned the walls of its base and did away with the iron plug, leaving a heavy, all-lead bullet that expanded to fit the rifling in guns better and could be easily and cheaply mass-produced.

What made the minie ball so harmful was its very design. A solid ball, when fired, passes through the human body but the minie ball flattens and expands, doing much more damage, shattering bones and tearing flesh; creating much larger, much more complex wounds. Both Union and Confederate soldiers used the minie ball in their muzzle-loading rifles.

I wanted to find a way to illustrate exactly how damaging these are to the human body. Below is part of a 1970s video from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. It is a series of ballistics experiments conducted by shooting bones embedded in gelatin blocks.

Warning: Even though the video shows the firing of a Minié ball through gel and bone, it isn’t hard to imagine what it would do to a human body and some may find it a bit gruesome.

You can find the full video that includes several different pistols, rifles, and types of ammunition on YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hQnVfyhVJ-Y&t=960s

Civil War Humor – General Sherman’s Air Support

Just had to share this image that a friend sent. I thought readers of the blog and those interested in this project would appreciate the humor. Her note said, “I found this and thought it would be helpful for your documentary.”

Image: Black and white photo of General Sherman on horseback. In the background above him is a fighter jet. Text reads, “A rare photo of an F-14D Tomcat providing Close Air Support for Union Troops during the American Civil War. Circa June 1863.”

For those of you who may be wondering, this is actually a fun photoshop of a Library of Congress photo taken by George Barnard in Atlanta, somewhere between September and November, 1864.

The Museum of the Confederacy

Whew! It’s been a little while but more than past time for an Update. Last month, we drove a couple of hours over to Richmond. We’re really working to get the most out of every trip so we visited the Museum of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis’ home (the White House of the Confederacy), and Chimborazo Confederate Hospital Museum. So actually, I’ve got enough information for several blog posts.

The Museum of the Confederacy is a small 3-floor museum, the topmost floor was dedicated to an exhibit on Flags of the Confederacy. There were several glass cases of uniforms and clothing of the period, including pieces specific to well known officers such as Robert E. Lee, John Bell Hood, etc. I am a bit disappointed in not finding much mention of what happened to disabled veterans both during and after the war but nevertheless it was an educational and informative visit. And we looked for footage that might be useful as B-roll.

“The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson” originally titled “The Heroes of Chancellorsville,” a gigantic oil on canvas done by Everett B.D. Julio. The painting depicts a romanticized final meeting between General Robert E. Lee and Lt. General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson before the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, where Jackson was wounded and later died. The original painting was acquired by the Museum of the Confederacy in 1992 and currently dominates their lobby area, even from its place in an alcove by the stairs.

This photo is from the July 3, 1913 50th Reunion of Gettysburg. This was a reenactment of Pickett’s Charge by the survivors. The musem has it blow up to poster size and it fills a wall. That day, thousands of spectators gathered to watch as the Union veterans took their positions on Cemetery Ridge, and waited as their old adversaries emerged from the woods of Seminary Ridge and started toward them again. First it was a walk, then they got faster, and faster, until it was an all out run. They converged as they had 50 years earlier at the stone wall but this time the Confederates were met with embraces of from the men they once battled.

And to close, I just want to give a quick snippet of video. This is from the headquarters tent of Robert E. Lee. While the display is exactly that, the items and personal effects actually belonged to Lee and went on campaign with him.

The Invalid Corps, the Assassination of President Lincoln, and the Hunt for John Wilkes Booth

So far, the documentary research is moving ahead slowly but steadily. In the next few weeks we will be seeking out more detailed and more specific images that are connected to Fort Stevens, the battle and Early’s raid. Unlike more famous (and more bloody) battles, there are fewer sketches, photos, and even first-person reminisces of the event.

Right now, like the rest of America, we are bombarded by election information. One can’t say we are not in a tumultuous time. Of course, in 1865 it was equally tense. President Lincoln has been dead for less than a week. The North is furious; the South, uneasy. An entire nation mourns but during this time (April 15 to April 26), there is a desperate manhunt for the conspiracy of assassins. What does that have to do with this project and the Invalid Corps? You might be surprised.

![]()

It is the night of April 14, 1865. President and Mrs. Lincoln decide to visit Ford’s Theater and see a play, “Our American Cousin.” A little after 10:25, John Wilkes Booth moves into position outside the President’s box. At the line in the play where the lead character says, “Don’t know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out.” John Wilkes Booth pulls out his derringer and fires a bullet into the back of the President’s head. He then leaps from the box to the stage, breaking his leg, but before he escapes through a back stage door, he delivers his last line from center stage: “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” (Thus always with tyrants!). Lincoln is dying, and his guard was nowhere to be seen.

It is the night of April 14, 1865. President and Mrs. Lincoln decide to visit Ford’s Theater and see a play, “Our American Cousin.” A little after 10:25, John Wilkes Booth moves into position outside the President’s box. At the line in the play where the lead character says, “Don’t know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out.” John Wilkes Booth pulls out his derringer and fires a bullet into the back of the President’s head. He then leaps from the box to the stage, breaking his leg, but before he escapes through a back stage door, he delivers his last line from center stage: “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” (Thus always with tyrants!). Lincoln is dying, and his guard was nowhere to be seen.

Provost Marshal James Rowan O’Beirne of the Invalid Corps was responsible for the safety of the President and his family. The night of Friday April 14, O’Beirne acceded to Mrs. Lincoln request he assign John Parker, a soldier with a record of bad performance to guard the President’s box. When Parker left his post, it cleared the way for John Wilkes Booth to shoot the President. That decision would haunt James O’ Beirne for the rest of his days.

At the start of the Civil War James O’Beirne was a Captain in the Irish Rifles, or the 37th New York Volunteers. During a bayonet charge at the Battle of Chancellorsville he is wounded several times, shot in the head, leg, and chest, puncturing a lung and paralyzing his right arm from shock.

“Guardedly the long line[s] groped through the woods. Glimpses only of the midnight moon flitted through the tall and sentineled forest … and gave a silver, ghoul-like sheen to the battalions. … Occasionally a soldier stumbled and pitched forward. Up! Forward again! No detention, no hesitation! How could he halt? The rear rank and others were striding behind him at close distance.” And then, “It seemed for the moment as if the doors of a blast-furnace had opened upon us.” There was terrible fire from both friend and foe.

O’Beirne survived the Chancellorsville campaign but when he appeared before a Medical Board, he was pronounced unfit for field service. He asked for a transfer into the Invalid Corps. On July 22, 1863, he was commissioned Captain into the Invalid Corps.

O’Beirne survived the Chancellorsville campaign but when he appeared before a Medical Board, he was pronounced unfit for field service. He asked for a transfer into the Invalid Corps. On July 22, 1863, he was commissioned Captain into the Invalid Corps.

“I was detailed on duty at the War Department here In Washington, in the provost marshal general’s bureau. I helped to organize the enlisted men of the Veteran Reserve Corps, composed of wounded soldiers and temporarily invalided men. There were twenty-two regiments of them. Then I was ordered by the Secretary of War to take charge of the provost marshal’s office of the District of Columbia.”

O’Beirne ended up playing a critical role in the defense of Washington during the Battle of Fort Stevens. He was the one who provided arms and equipment to soldiers, clerks, and any man willing to take arms to defend the city. He stood with Lincoln on the ramparts as sniper fire whizzed past them from Jubal Early’s Confederate troops. And when it was over, O’Beirne was the one who ensured care for the wounded and saw to the prisoners.

But even then his job wasn’t done. Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, ordered him to chase down Early’s men as they retreated back through Maryland to Virginia. For his efforts, he was eventually promoted to Provost Marshal for the District of Columbia which put him in charge of the President’s safety on that fateful night. Saturday, April 15th, 1865 at 7:30 Abraham Lincoln died and from that moment on O’Beirne was committed to hunting down the President’s killers.

“When I went to get Vice President Johnson and bring him to the bedside of [dying] Lincoln, as I had been ordered to do, he lived at the Kirkwood House, on the spot where now stands the Raleigh Hotel. When I told Mr. Johnson that Lincoln had been shot he informed me his suspicions had been aroused that night at the Kirkwood House. Mr. Johnson had heard footsteps for hours in the room above him. In the morning I went to the hotel again, and in the room which had been let to George Atzerodt, I found Booth’s hank book, a large bowie knife, a Colt navy revolver, and a handkerchief with the initial H embroidered on it. This turned out to be evidence of the complicity of Booth, Herold and Atzerodt, and established the fact that there had been a plot.”

“When I went to get Vice President Johnson and bring him to the bedside of [dying] Lincoln, as I had been ordered to do, he lived at the Kirkwood House, on the spot where now stands the Raleigh Hotel. When I told Mr. Johnson that Lincoln had been shot he informed me his suspicions had been aroused that night at the Kirkwood House. Mr. Johnson had heard footsteps for hours in the room above him. In the morning I went to the hotel again, and in the room which had been let to George Atzerodt, I found Booth’s hank book, a large bowie knife, a Colt navy revolver, and a handkerchief with the initial H embroidered on it. This turned out to be evidence of the complicity of Booth, Herold and Atzerodt, and established the fact that there had been a plot.”

Also included was a map showing Atzerodt’s escape route. O’Beirne followed and ensured his capture. One day passed, and then another, and another. The search for Booth through the countryside was proving fruitless. But O’Beirne followed his instincts and explored intelligence that Booth had crossed over to Virginia. Unfortunately, he was denied permission to search the Port Royal area and was recalled to Washington.

Although Colonel Lafayette Baker and his 16th New York Cavalry, who took over the search, garnered the praise and the place in history for eventually capturing Booth, it was James O’Beirne, Invalid Corps, and his detective work that lead them there.

Thanks for being a part of the Invalid Corps Team!

Resources

In Pursuit of Lincoln’s Assassin: Roscommon-Born James Rowan O’Beirne

James Rowan O’Beirne and Pursuit of John Wilkes Booth

The Irish Rifles at the Battle of Chancellorsville

*As stated previously, for the purposes of this project (and to keep confusion to a minimum) we will be using the term Invalid Corps throughout the time period of the corps commissioning rather than Veteran Reserve Corps.

Elizabeth Thomas, Owner of Fort Stevens

Today is President’s Day, February 12 was Lincoln’s birthday, and this entire month is #BlackHistoryMonth. As such, it seems like a good time to post a quick update. We’ve been very busy! We’re currently putting together the segment-by-segment breakdown for our short film with preliminary language and quotes. The goal is to use this frame and outline to recognize gaps in our narrative and to better steer our research. In addition, we’re still scouring archives and records for stories from Invalid Corps members themselves.

Today is President’s Day, February 12 was Lincoln’s birthday, and this entire month is #BlackHistoryMonth. As such, it seems like a good time to post a quick update. We’ve been very busy! We’re currently putting together the segment-by-segment breakdown for our short film with preliminary language and quotes. The goal is to use this frame and outline to recognize gaps in our narrative and to better steer our research. In addition, we’re still scouring archives and records for stories from Invalid Corps members themselves.

On Saturday, we visited with the National Park Service who hosted a fantastic presentation on Elizabeth Thomas, the original owner of the property that became Fort Stevens, which of course, played such a critical role in our project. Although Elizabeth’s story is only tangentially connected, I wanted to share with you what we learned about this exceptional woman.

![]()

Elizabeth Proctor Thomas was born in the early 1800s. She lived in Brightwood, a community of free blacks in northwest Washington, D.C. (I believe it was then called Vinegar Hill). Elizabeth’s property was of a significant size and value (88 acres) with a barn, garden, orchard, and a two-story wooden house. And because of its location on a hill beside the Seventh Street Turnpike (now Georgia Avenue), they controlled the major tributary leading into Washington from the north.

Elizabeth Proctor Thomas was born in the early 1800s. She lived in Brightwood, a community of free blacks in northwest Washington, D.C. (I believe it was then called Vinegar Hill). Elizabeth’s property was of a significant size and value (88 acres) with a barn, garden, orchard, and a two-story wooden house. And because of its location on a hill beside the Seventh Street Turnpike (now Georgia Avenue), they controlled the major tributary leading into Washington from the north.

As such, with the advent of the Civil War, Elizabeth would lose her farm to the Union army when they took the land to build what would eventually become Fort Stevens. As she later told a reporter, one day soldiers “began taking out my furniture and tearing down our house.” As the soldiers were German immigrants, they couldn’t understand Thomas, nor could she understand them.

“I was sitting under that sycamore tree with what furniture I had left around me. I was crying, as was my six months-old child, when a tall, slender man dressed in black came up and said to me, ‘It is hard, but you shall reap a great reward.’”

It was President Abraham Lincoln.

When Jubal Early’s Confederate army marched to Washington and stood at the very gates of Fort Stevens, Elizabeth Thomas did not flee with other refugees. She did not hide with civilians. She stayed. Affectionately nicknamed “Aunt Betty” by her soldiers, she continued to cook and do laundry for them. When battle was imminent, she carried ammunition back and forth on the walls of the fort itself. And as the President stood on the fortifications, she kept her old shotgun by her side to kill any “Rebs” who would try to harm her Lincoln.

Even after the war Elizabeth continued to be a civic leader doing much to shape the DC community. Her warmth and courage was respected by many. In fact, for many years after the war, when the Grand Army of the Republic held their reunions in the city, they would do so at her house – with the African American woman who was brave enough, who cared enough, to fight beside them to save the city.

![]()

Pretty powerful stuff and a great example of amazing stories of men and women that can and should be told before they are lost to history. And because of you we shall endeavor to capture similar stories about the Invalid Corps. Special thanks to National Park Service Ranger Kenya J. Finley and Patricia Tyson of the Military Road School Preservation Trust and Female RE-Enactors of Distinction.

A quick note this is the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service. NPS always has great programs – history, nature, culture – and they’ve been staunch supporters of our own Invalid Corps project with information and advice, so I have to give a shout out and encourage you to spend some time this year and #FindYourPark.

Resources

Find out more about Elizabeth Proctor Thomas from the National Park Service: http://www.nps.gov/cultural_landscapes/People-Thomas.html

A wonderful detailed article about Elizabeth Thomas from the Civil War Round Table of Washington DC: http://files.cwrtdc.org/62-1-Newsletter-September2012.pdf

You can also read more about her and how she was thought of from the Afro-American, a local newspaper (August 30th, 1952): https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2211&dat=19520830&id=uOklAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ffYFAAAAIBAJ&pg=3002,632358&hl=en

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s #Christmas Bells and the #CivilWar

We were fortunate enough to visit Shepherdtown, WV for their Second Annual Civil War Christmas. Check out my previous post for details and images. However, we missed their shadow play based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “Christmas Bells.”

It has long been a favorite carol of mine; what I did not know, was the story behind the poem. There is a sad melancholy attached to the piece that is impossible to miss, and yet it still ends on a happy note with that single abiding human emotion that links us all together – hope.

So, in celebration and in contemplation for this Christmas week, please find the words to Longfellow’s poem below and a beautiful video put together by SpiritandTruthArt.

Happy Holidays from all of us on the Invalid Corps Team and wishing you always, “peace on Earth, and goodwill to men.”

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till, ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said;

”

For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead; nor doth he sleep!

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men!

A Civil War Christmas in Shepherdtown, West Virginia

This weekend, we went out to Shepherdtown, WV to see if we could get a little extra footage. This was the second annual “Civil War Christmas in Shepherdstown.” Organized by the Shepherd University Department of History, the George Tyler Moore Center, and the Shepherdtown Visitors Center there were a plethora of activities and things to see. We got lost a few times. I am not sure the maps were created for out-of-towners like us, either that, or we just had a terrible sense of direction. I suspect the latter.

There was some great living history and we took a tour of the Conrad Shindler House, which houses the George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War, and finished off our day at the Ferry Hill plantation. Both of the buildings had portions that existed during the Civil War. We also saw the making of 19th-century ornaments, but sadly missed the shadow play that was scheduled to highlight Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “Christmas Bells.” Below are a few photos from the day.

#Thanksgiving in the Civil War: a Proclamation from #History

It seems fitting that on this day of giving thanks and thoughtful reflection to wonder just a little bit about Thanksgiving in the Civil War. The first Thanksgiving was in the 1600s-ish but the tradition didn’t really catch on until the Civil War. On July 15, Lincoln issued a proclamation declaring a national day of thanksgiving for October 3rd, 1863.

By the President of the United States of America.

A Proclamation.

The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever watchful providence of Almighty God.

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign States to invite and to provoke their aggression, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict; while that theatre has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.

Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defence, have not arrested the plough, the shuttle or the ship; the axe has enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege and the battle-field; and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with large increase of freedom.

No human counsel hath devised nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity and Union.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this Third day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and of the Independence of the Unites States the Eighty-eighth.

By the President: Abraham Lincoln

William H. Seward,

Secretary of State

Four Letters from the Civil War – William Child, JR Montgomery, Alva Marsh, and an Unknown Confederate Soldier

One of the most moving remnants from the #CivilWar are the letters to soldiers and from the soldiers to their loved ones. I’ve written previously about the importance of and impact of mail during this time but thought I might include a couple of examples. One of the best resources for anything Civil War is the National Park Service. They have some fantastic educational materials suitable for classrooms, including a collection of letters and some fantastic videos. Although only one of the examples below are from men in the Invalid Corps, they are letters from soldiers themselves giving us insight into a moment in their lives.

William Child, Major and Surgeon with the 5th Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers

William Child, Major and Surgeon with the 5th Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers

September 22, 1862 (Battlefield Hospital near Sharpsburg)

My Dear Wife;

Day before yesterday I dressed the wounds of 64 different men – some having two or three each. Yesterday I was at work from daylight till dark – today I am completely exhausted – but stall soon be able to go at it again.

The days after the battle are a thousand times worse than the day of the battle – and the physical pain is not the greatest pain suffered. How awful it is – you have not can have until you see it any idea of affairs after a battle. The dead appear sickening but they suffer no pain. But the poor wounded mutilated soldiers that yet have life and sensation make a most horrid picture. I pray God may stop such infernal work – through perhaps he has sent it upon us for our sins. Great indeed must have been our sins if such is our punishment.

Our Reg. Started this morning for Harpers Ferry – 14 miles. I am detailed with others to remain here until the wounded are removed – then join the Reg. With my nurses. I expect there will be another great fight at Harpers Ferry.

Carrie I dreamed of home night before last. I love to dream of home it seems so much like really being there. I dreamed that I was passing Hibbards house and saw you and Lud. in the window. After then I saw you in some place I cannot really know where -you kissed me – and told me you loved me – though you did not the first time you saw me. Was not that quite a soldier dream? That night had been away to a hospital to see some wounded men – returned late. I fastened my horse to a peach tree – fed him with wheat and hay from a barn near by – then I slept and dreamed of my loved ones away in N.H.

Write soon as you can. Tell me all you can about my business affairs and prospects for the future in Bath. Will Dr. Boynton be likely to get a strong hold there. One thing sure Cad, I shall return to Bath – if I live – and spend my days there. I feel so in that way now. Give me all news you can. Tell Parker and John and the girls to write although I can not answer them all. Tell Parker I will answer his as soon as I can.

In this letter I send you a bit of gold lace such as the rebel officers have. This I cut from a rebel officers coat on the battlefield. He was a Lieut.

I have made the acquaintance of two rebel officers – prisoners in our hands. One is a physician – both are masons – both very intelligent, gentlemanly men. Each is wounded in the leg. They are great favorites with our officers. One of them was brought off the field in hottest of the fight by our 5th N.H. officers – he giving them evidence of his being a mason.

Now do write soon. Kisses to you Clint & Kate. Love to all.

Yours as ever

W.C.

____________________

James Robert Montgomery, Signal Corps, Heth’s Division, 3rd Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, C.S.A.

May 10, 1864 (Spotsylvania County, Virginia)

Dear Father

This is my last letter to you. I went into battle this evening as courier for Genl. Heth. I have been struck by a piece of shell and my right shoulder is horribly mangled & I knowdeath is inevitable. I am very weak but I write to you because I know you would be delighted to read a word from your dying son. I know death is near, that I will die far from home and friends of my early youth but I have friends here too who are kind to me. My friend Fairfax will write you at my request and give you the particulars of my death. My grave will be marked so that you may visit it if you desire to do so, but it is optionary with you whether you let my remains rest here or in Miss. I would like to rest in the grave yard with my dear mother and brothers but it’s a matter of minor importance. Let us all try to reunite in heaven. I pray my God to forgive my sins and I feel that his promises are true that he will forgive me and save me. Give my love to all my friends. My strength fails me. My horse and my equipments will be left for you. Again, a long farewell to you. May we meet in heaven.

Your dying son,

J.R. Montgomery

The video below from the NPS tells a bit more about Montgomery’s story. You can also see/hear the letter in Ric Burn’s Civil War documentary, “Death and the Civil War.”

____________________

Alva H. Marsh, Corporal, Company E, Seventh Michigan Volunteer Infantry

Alva H. Marsh, Corporal, Company E, Seventh Michigan Volunteer Infantry

February 10, 1864 (Fairfax Seminary Hospital, Virgnia)

Dear Mother I take my pen to inform you that I got safe to my home in the hospital on Sunday at two o clock today I have been down to Alexandria to get some papers and envelopes so as to write to you I have been examined twice since I came back from home the doctor says that I will always be lame

I am thankful to think it is no worse then it is I think they will put me in the Invalid corps but I can stand it in the condemned Yankees for the balance of my time if they only ask me to stay for the next three months I can get out by [illegible] next if they want to stay all summer in the invalid corps I shant do it for I am sick of the war I want To stay at home some of my life don’t you think so Frank I suppose you are at home yet

I want you to take good care of the girls for me I was homesick when I began to [illegible] the hills of Virginia I tell you but it is of no use to have the blues here for a fela has got to stay but I cant write any more at present this from Alwah Sarah you must be a good little girl until I come home I don’t mean Sarah Hathaway for I know that she will be good you know I think so How is Alice and Miss [illegible] write to me as soon as you can

from A W Marsh

*from the University Archives & Historical Collections, Michigan State University

____________________

Unknown Confederate Soldier

July 3, 1863 (Gettysburg, PA)

Dr. Holt worked in a field hospital behind Seminary Ridge. He spoke of the unforgettable courage of a wounded soldier stating, “His left arm and a third of his torso had been torn away and he dictated a farewell letter to his mother.” It read simply,

“This is the last you may ever hear from me. I have time to tell you that I died like a man. Bear my loss as best you can. Remember that I am true to my country and my greatest regret at dying is that she is still not free and that you and your sisters are robbed of my youth. I hope this will reach you and you must not regret that my body cannot be obtained. It is a mere matter of form anyhow. This letter is stained with my blood.”

*from http://www.brotherswar.com/ – The epic story of the Battle of Gettysburg as told in the participants’ own words.

Who Held the Saw: Discovering Mary Walker, Civil War Army Surgeon – From Julia Marie Myers

It was Day who first told me of the Invalid Corps. I had never heard of it before. I remember listening with rapt attention as she painted a picture of the night when members of the Invalid Corps defended the Capitol against a Confederate army of 15,000. It was a classic, incredible story epic.

Intrigued, I went and did more research. It began to boggle my mind the pure numbers of soldiers injured during the war — we all know that in theory, but in literal, stark numbers … approximately 17,300 Union casualties at the Battle of Chancellorsville alone (the one where Stonewall Jackson was injured, later dying from his wounds), with almost 10,000 of those being wounded, rather than killed or missing[1]. Ten-thousand. Ten-thousand bodies, strewn about, amongst those who have already perished. How do you even know which ones are still alive?

“Near by, the ambulances are now arriving in clusters, and one after another is call’d to back up and take its load. Extreme cases are sent off on stretchers. The men generally make little or no ado, whatever their sufferings. A few groans that cannot be suppress’d, and occasionally a scream of pain as they lift a man into the ambulance. To-day, as I write, hundreds more are expected, and to-morrow and the next day more, and so on for many days. Quite often they arrive at the rate of 1000 a day.” – Walt Whitman, Specimen Days, Ch. 33[2]

With so many soldiers and varieties of injuries, I began looking into the army surgeons who had to navigate this chaos — the ones who had to determine how to triage the patients, who ultimately had to “wield the saw.” One particular surgeon stood out.

Mary Walker’s story unfolded in front of me as I flipped through the virtual pages of the internet, piecing together information about her career. She was clearly a “disruptive” person — the only woman at the time enrolled in her medical degree program at Syracuse, the first woman surgeon ever to be employed by the US Army.[3]

As I read more about Mary, I found her story incredibly modern. Mary wore men’s clothes. She surely faced discrimination and ridicule for this choice — and indeed on more than one occasion she was arrested for “impersonating a man.”[4] It strikes me as incredible that she existed so long ago, but that she could just as easily be a next door neighbor of mine, who faces similar concerns and judgments about her identity today. We are divided by centuries of time, but when I look at her, I see a saturated, piercing image of the modern world staring back.

Mary’s story as well as the stories of the members of the Invalid Corps inspired me to write my own short fiction film inspired by both historical narratives, for which I am now beginning the pre-production process. I felt that Mary’s role in disrupting the status quo of women, but also in standing on her own as an influential person regardless of her gender, paralleled so beautifully with the story of these men of the Invalid Corps, who defied not only their labels as “cowards” and “cripples,” but who rose up to show that they mattered, fully and fundamentally, as people.

It has been a great pleasure intertwining these stories together in a creative way, and it has been a perfect complement to my working with Day on her documentary on the Invalid Corps. Every day, we are learning more and more, and it only makes me more excited to share what we have discovered, and what we are creating, with you.

Don’t forget to visit our “The Invalid Corps and the Battle of Fort Stevens” Kickstarter:

(https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/dayalmohamed/the-civil-war-invalid-corps-and-the-battle-of-fort)!

Please share widely. We need you to help get the word out about this documentary!

[1] http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/chancellorsville.html?tab=facts

[2] http://www.bartleby.com/229/1033.html

[3] http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/rr/s01/cw/students/leeann/historyandcollections/history/pathbreakers/marywalker.html

[4] https://www.nlm.nih.gov/changingthefaceofmedicine/physicians/biography_325.html

Kickstarter First Stretch Goal Revealed! – Civil War Mail

A quick Update from our Invalid Corps and the Battle of Fort Stevens Kickstarter. We’ve reached 90%! We are thrilled and humbled by the support we’ve received. And now we have 13 more days to reach the full amount. Considering the closeness to our goal, we thought it prudent to unveil our first Stretch Goal.

Our first Stretch Goal is a simple one, and one we hope is in relatively easy reach: $8,000. We hope to entice more people to support this project and/or to consider backing at a higher level. Why? Because at its heart, the Invalid Corps documentary is about the content and the stories of these men. Additional funding will allow us to begin to pay for direct production and have higher production values – To get this done right.

It means being able to afford things like a professional sound editor; some compensation for musicians (we have a composer so this project will have an original score but musicians have to eat too); and being able to send a full crew out for additional interviews with historians and descendants of Invalid Corps members. As for those who may be wondering, what additional reward that may entail, I give you the paragraphs below. 🙂

Mail has always been very important to soldiers. During the Civil War, these fragile notes are what connected families and in many ways have continued to connect military families, even today. These letters tell a much more intimate story than our textbooks of generals and battles. And of course, as we know, many soldiers carried letters in their pockets, to be forwarded to loved ones if they were killed in action.

About 45,000 pieces of mail per day were sent through Washington D. C. from the eastern theater of the war, and about double that in the west, through Louisville. According to Bell Wiley’s “Billy Yank,” a civilian worker with the U. S. Sanitary Commission, who visited a number of units, reported that many regiments sent out an average of 600 letters per day, adding up to more than 8 million letters travelling through the postal system per month. Franklin Bailey wrote to his parents in 1861, that getting a letter from home was more important to him than “getting a gold watch.” (via Dave Gorski at CivilWarTalk.com)

In recognition of the role that letters played, with this first stretch goal, we will send each backer (at the $25 and up level) an actual piece of PHYSICAL mail. They’ll receive a custom postcard of Invalid Corps imagery via the US Postal Service. Sent the same way families mailed letters more than 150 years ago, this is our “letter,” in thanks.

Resources: http://about.usps.com/news/national-releases/2012/pr12_civil-war-mail-history.pdf

Don’t forget to visit our Kickstarter! We need your to help get the word out about this documentary.

Black Civil War Soldiers with Injuries, Chronic Conditions, and Disabilities

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

– Frederick Douglass

As a woman of color, while doing research on the Invalid Corps one of the things that I wondered about was what happened to African-American injured soldiers? In fact, while doing research on the Invalid Corps it occurred to me that I had not seen one image of an injured black soldier. So, I started where everyone does: Google. I put in “Black Civil War Soldier” and found several images. I added the term “Injured” and I found a Thomas Nast illustration from Harpers Weekly came up a lot.

Considering that more than 180,000 African Americans served, making up about 10% of the Union Army, and more than half survived the war, I would think there would be some evidence of their presence and their survival post injury. I changed to the word “amputee.” Granted, it’s very specific but so far I had not been able to find ANY images of injured black soldiers.

With that change, one image came up. Only one. It’s a photo of Private Lewis (sometimes spelled Louis) Martin, of Company E, 29th United States Colored Troops. His photo was found glued to his certificate of disability for discharge by Civil War Conservation Corps volunteers while compiling records at the National Archives. His wounds were described in his discharge form: “Loss of right-arm and left-leg by amputation for shell and gunshot wounds received in battle at Petersburg on July 30, 1864 in charging the enemies works. In consequence of which is totally disabled for military service and civil occupation wholly.” He was a forgotten Civil War veteran for more than 120 years, buried in the paupers section of Oak Ridge Cemetery in an unmarked grave until a community effort was made to mark his grave with a tombstone.

From what is known, Private Lewis Martin was born in Arkansas, a slave, but somehow became free, enlisted in Illinois in February of 1864. A muster roll record lists his place of birth as Arkansas, his age as 24 years, his height as 6 feet, 2 inches, and his occupation as a farmer. A few months later he took part in the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg, Virginia and was wounded, resulting in the amputations. He was sent to the General Hospital at Alexandria, Virginia, then later transferred to Harewood Hospital in Washington, DC before finally being discharged. He returned to Illinois.

After that, his story is hard to follow, but from what I can find, it is a sad tale. He obviously was unable to work, and was the victim of discrimination and public humiliation. He became an alcoholic. It would seem his obituary and articles in several papers made mention of it:

Died from Exposure & Drink

Louis Martin, a Colored Man, Dies Alone

At FindaGrave the IL State Register’s obituary reads:

A negro named Lewis Martin, who is well known in this city as the one-legged and one-armed old soldier, was found dead yesterday morning in his bed. He resided in a house, corner of Lincoln avenue and Jefferson street, and up to a short time ago he had been having a white woman at his home as a housekeeper, but she left him recently and he had since lived alone. About 7 o’clock yesterday morning, Mrs. Carrie Boone, colored, who came to the house frequently to look after him, found him dead. Mrs. Boone immediately notified some of the neighbors.

He was a private in the Twenty-ninth Illinois volunteers during the war, and received a pension of $72 per month for the loss of his limbs and one eye in the army. He received some time ago back pension money amounting to $6,500, a portion of which he invested in property on West Jefferson street, including the place where he lived. He also had some money saved up. He was about 45 years of age, and has two brothers residing in Alton, who have been notified of his death. IL State Register, Springfield, IL 1-27-1892

On November 2, 2013, citizens from the Springfield community held a ceremony honoring Private Martin. A marker for his grave was erected and Civil War re-enactors presented the colors; a 21-gun salute and the playing of “Taps,” all the things Lewis did not get when he died. Considering, the dedication was exactly 2 years ago today, it seemed pertinent to write and reflect on Private Lewis Martin, his service and his sacrifice.

Some great resources, articles, and posts of Private Martin’s story

Dave Bakke: Black Civil War veteran’s grave identified at Oak Ridge – http://www.sj-r.com/article/20120516/NEWS/305169913/?Start=1

They were Men who Suffered and Died – http://usctchronicle.blogspot.com/2011/01/they-were-men-who-suffered-and-died.html

Public Comes Through for Civil War Icon – http://www.sj-r.com/x452551251/Public-comes-through-for-Civil-War-icon#ixzz2ieFsiaGJ

Teaching With Documents: Preserving the Legacy of the United States Colored Troops – http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war/article.html

Please don’t forget we are in the middle of our Kickstarter to raise funds to tell the story of the Invalid Corps; of soldiers with disabilities who continued to serve: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/dayalmohamed/the-civil-war-invalid-corps-and-the-battle-of-fort

Civil War Myths and Mysteries Quiz – Courtesy of @CivilWarTrust

I couldn’t resist a quick post in recognition of the season. So for Halloween, lets take a look at some myths and mysteries of the Civil War. Can you separate fact from fiction? The Civil War Trust has a great little quiz. (Actually, their whole site is fantastic). But for tonight, start with the quiz. 🙂 Try it out! Just click on the image below, answer a few questions, and let us know how you scored!

And if you really must know…I got a 70%. Obviously, I need to do a whole lot more reading and research!

And of course, our Kickstarter for the documentary film, “The Invalid Corps and the Battle of Fort Stevens” is still running this month: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/dayalmohamed/the-civil-war-invalid-corps-and-the-battle-of-fort

Soldiers’ Stories: Sergeants Durgin and Wray

For William Durgin of Maine, April 20, 1865 was a typical day. He was garrisoned at the Camp Frye Barracks in Washington, D.C., assigned with the 10th Veterans Reserve Corps. His typical duties with the regiment consisted of nothing more than garrison duty after suffering from rheumatism in his arms and being struck in the ankle with a cannonball during the amphibious landing at Fernadina, Florida in 1862. Yet, when he received his orders for that day, they looked far different from his daily duties. The order read as follows:

Special Order No. 88

Pursuant to orders from Headquarters, 1st Brigade Veteran Reserve Corps requiring four First Sergeants should be selected with reference to their age, length of service and good soldierly conduct for escort duty to the remains of President Lincoln to Springfield, Illinois.

1st Sergeant William W. Durgin of Company F 10th Regiment V.R.C. is hereby detailed for that duty and will report to Capt. McCamly 9th Regiment Vet. Res. Corps at Camp Frye at 9:00 o’clock A.M. this day.

By command ofMajor George Bowers Commanding Regiment

From his clerical duties at Camp Frye Barracks, Durgin’s place in history rose greatly as he became one of Lincoln’s pallbearers, traveling across the nation with the casket. His war-record carries on his roll call for April 1865 “Absent – on escort duty with remains of President Lincoln.”

While Durgin seems to be a typical soldier offered the honor as a token of great luck, in many ways the assignment was and did boost the prestige of one of the most neglected regiments in the U.S. Army: the Veterans Reserve Corps (VRC).

Created in 1863, the VRC started as the Invalids Corps, and began as a project to give disabled veterans like Durgin a second chance at active service. Yet their corps did not go unscathed. Other soldiers derided the corps as a group of cowards and rejects; the initials of the Invalids Corps matched a stamp of the Quartermaster’s Department that stood for “Inspected – Condemned.” Soon after, to boost the morale of recruits and entice more volunteers, it was renamed “Veterans Reserve Corps.” The disabled veterans that re-enlisted were assigned various rear-echelon duties, ranging from guard duty to censoring mail.

To honor one of the corps members as a pallbearer presented in a greater sense a place for disabled soldiers in American military history alongside regular soldiers in memorializing the Civil War, and recognizes the potential of disabled veterans, or civilians, as capable individuals that can still contribute despite their sacrifice.

Enlistment in the corps did not always entail monotonous, clerical duties. For Sergeant William Wray, fate would lead to a reprisal of his combat duties. After losing his right eye and parts of his nose at Fredericksburg, Wray joined the 1st Veterans Reserve Corps. While stationed at Fort Stevens, he miraculously found himself at the center of a surprise attack by a corps of 10,000 men led by Jubal Early. In the midst of battle, while a number of his VRC comrades were confused and scattered, Wray rallied his men to the defenses during a critical attack, and helped prevent the fort from falling. Although his actions did not go recognized until much later, with some speculation regarding the fact that he was a member of the undesirable VRC, Wray was eventually awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions.

After the Civil War, programs for injured soldiers and disabled veterans returned around World War I, when the massive amounts of casualties and disabling injuries permitted for the resurrection of the Veterans Reserve Corps. In the age of modern warfare, disabled veterans have been able to carve a niche for themselves with the Continuation on Active Duty program, allowing wounded soldiers to serve their country within the limits of their abilities. Thus, heroes like Sergeants Durgin and Wray show what makes a soldier a great leader and a hero is not how well or straight a soldier stands, but what a soldier stands for in fighting for their country.

Jonathan van Harmelen is currently studying American History at Pomona College, and has conducted research with Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. He also works at Pomona College as manager for the Orchestra and as assistant to the History Department. He enjoys collecting military antiques, playing drums, and attempting to learn French, German, and Dutch all at once.

Please don’t forget we are in the middle of our Kickstarter to raise funds to tell the story of the Invalid Corps; of soldiers with disabilities who continued to serve:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/dayalmohamed/the-civil-war-invalid-corps-and-the-battle-of-fort

Civil War Encampment

Just a quick collection of images from the Civil War Union encampment and funeral parade. First up though is a collage from this whole weekend. 🙂

Collage Image: Civil War Union soldiers with reversed weapons. The Leviathan steam locomotive. A drummer. An older soldier with the American flag behind him. In the center, the seal from the Lincoln funeral car, the United States – an eagle with wings outstretched.

Society for Disability Studies and the Invalid Corps as “Hidden #Disability History”

We were very proud to present at this year’s Society for Disability Studies national conference in Atlanta, Georgia. The Society for Disability Studies (SDS) is a scholarly organization dedicated to promoting disability studiesand their conference examines “multiple and significant possibilities at the intersections of disability and (getting it) right/s” with “hundreds of participants [who] gather every year to share expertise, perspectives, and community.” The story of the Invalid Corps is a part of disability history and it was great speak on a panel about soldiers with disabilities and this “hidden history.”

We were very proud to present at this year’s Society for Disability Studies national conference in Atlanta, Georgia. The Society for Disability Studies (SDS) is a scholarly organization dedicated to promoting disability studiesand their conference examines “multiple and significant possibilities at the intersections of disability and (getting it) right/s” with “hundreds of participants [who] gather every year to share expertise, perspectives, and community.” The story of the Invalid Corps is a part of disability history and it was great speak on a panel about soldiers with disabilities and this “hidden history.”

Although most of the presentation was an introduction to the Invalid Corps and their role in the Civil War, I thought I’d blog a little bit about how I opened the talk. An aspect of “Black History Month” has always struck me: how little of history has been captured that includes the contributions, heroism, sacrifice, and inventions of African Americans. The same for women. History has primarily been written by a certain class of individuals, who were likely men, and white. What that means is that history doesn’t often include mention of minorities. That includes disability.

So, when speaking with the audience I wanted to highlight “bright and shining” examples of disability that, because of the way we view the world, have had their disability erased and that part of the story goes untold. I wanted to include examples of men who meet that description, and although they were never part of the Invalid Corps, they were individuals with disabilities who many people do not know had disabilities – hidden disability history.

Oliver Otis Howard

O. O. Howard is known as a man who was a general in the civil war. He is known as the first head of the Freedmen’s Bureau who was dedicated to supporting the new independence of freedmen. He is known as the founder of Howard University. But what I discovered is that many graduates of the institution don’t realize (I’ve spoken to almost a dozen at this point) that he was also a man with a disability. General Howard lost his right arm at the Battle of Fair Oaks in 1862 when he was still a brigade commander. Disability was so ubiquitous that it was seldom mentioned; everyone had a brother, son, father, husband, or neighbor who had been injured in battle. And over time, this piece of history becomes lost. While it may not seem important in the “broad picture,” when it comes to recognition of disability and its place within our society, knowing this history suddenly becomes quite important.

O. O. Howard is known as a man who was a general in the civil war. He is known as the first head of the Freedmen’s Bureau who was dedicated to supporting the new independence of freedmen. He is known as the founder of Howard University. But what I discovered is that many graduates of the institution don’t realize (I’ve spoken to almost a dozen at this point) that he was also a man with a disability. General Howard lost his right arm at the Battle of Fair Oaks in 1862 when he was still a brigade commander. Disability was so ubiquitous that it was seldom mentioned; everyone had a brother, son, father, husband, or neighbor who had been injured in battle. And over time, this piece of history becomes lost. While it may not seem important in the “broad picture,” when it comes to recognition of disability and its place within our society, knowing this history suddenly becomes quite important.

Mathew Brady

Mathew Brady, the photographer of the Civil War. The man whose thousands of scenes of war give us the vision of the time. We all know the images. We all have seen at least one picture attributed to him (or more likely, his company.) Mathew Brady had a disability. Although Brady had his own studio and permission from President Lincoln himself to photograph the battlefield sites, many of the photos were in fact, taken by his assistants. Brady had an eye condition and his vision began to deteriorate in the 1850s. He was almost totally blind the last few years of his life.

Mathew Brady, the photographer of the Civil War. The man whose thousands of scenes of war give us the vision of the time. We all know the images. We all have seen at least one picture attributed to him (or more likely, his company.) Mathew Brady had a disability. Although Brady had his own studio and permission from President Lincoln himself to photograph the battlefield sites, many of the photos were in fact, taken by his assistants. Brady had an eye condition and his vision began to deteriorate in the 1850s. He was almost totally blind the last few years of his life.

John S. Pemberton

And of course, because we were in Atlanta, I had to mention John Pemberton, inventor of Coca-Cola. Yes, he too had a disability. A Confederate Lieutenant Colonel, he was wounded at the Battle of Columbus, in what was, arguably, the last battle of the war. Shot and then slashed across the chest with a saber, the wound gave him chronic pain. This led to a morphine addiction, ailment that was so common among veterans it was called the “soldier’s disease.” Pemberton invented Coca-Cola as an alternative to the highly addictive morphine. In his own words: “free from opium…a remedy to meet the urgent demand for a safe and reliable medicine.” Whether to address his addiction and/or to manage the pain from his war wounds, Pemberton, inventor of Coca-Cola, was also a man with a disability.

And of course, because we were in Atlanta, I had to mention John Pemberton, inventor of Coca-Cola. Yes, he too had a disability. A Confederate Lieutenant Colonel, he was wounded at the Battle of Columbus, in what was, arguably, the last battle of the war. Shot and then slashed across the chest with a saber, the wound gave him chronic pain. This led to a morphine addiction, ailment that was so common among veterans it was called the “soldier’s disease.” Pemberton invented Coca-Cola as an alternative to the highly addictive morphine. In his own words: “free from opium…a remedy to meet the urgent demand for a safe and reliable medicine.” Whether to address his addiction and/or to manage the pain from his war wounds, Pemberton, inventor of Coca-Cola, was also a man with a disability.

The Invalid Corps story is a part of this “hidden history” and for the SDS attendees, one that they were excited to learn more about. I hope to be able to show their story at the 2016 conference!

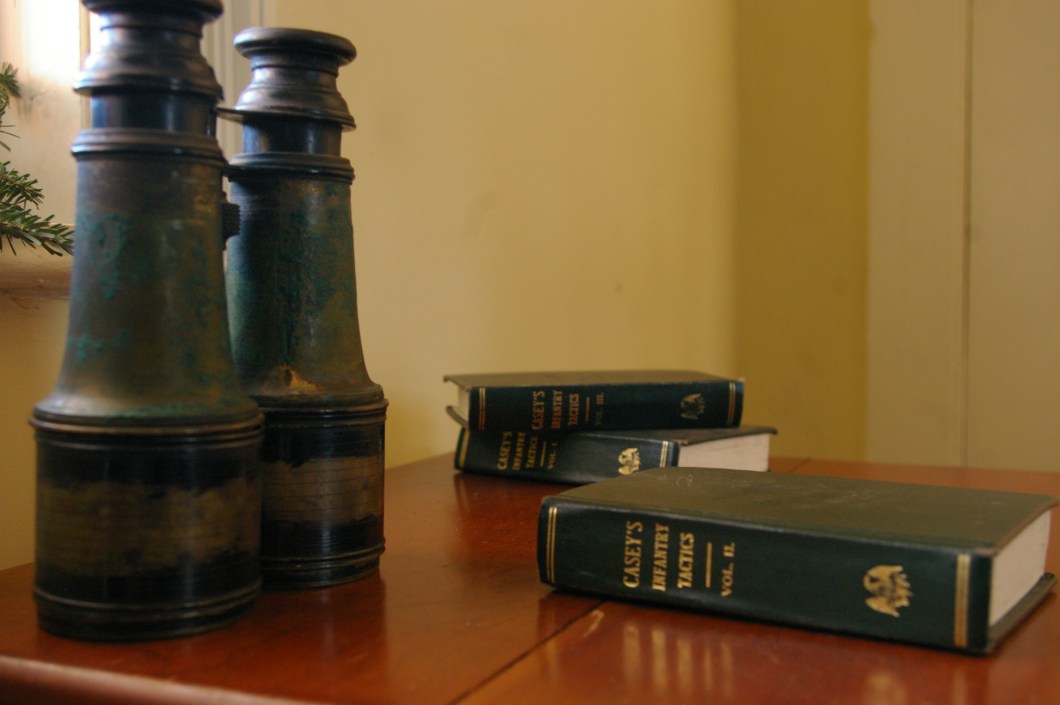

Background Reading and Useful Books (#InvalidCorpsFilm)

I’ve been doing quite a lot of reading to make sure we are solidly grounded in the history of these events. It has been a fun challenge in some ways. The information is split up in multiple places: Stories about men injured during the war is in one place, information on the Battle of Fort Stevens is in another, and information on the Invalid Corps itself is somewhere else again. Pulling it all together is the part that is most exciting.

I’ve looked at several websites, explored library collections, spoken to people in online forums, and perused journal articles as well as general articles for the public. But I thought it might be useful to just list some of the actual books that I’ve been reading. Granted, not all fit the topic fully, but they’ve all been very informative and have helped immensely.

So, in no particular order, to date I have read:

- Jubal Early’s Raid on Washington by Benjamin Franklin Cooling III

- The Day Lincoln was Almost Shot: The Fort Stevens Story by Benjamin Franklin Cooling III (this one is my favorite)

- Lincoln Under Enemy Fire by John Henry Cramer

- Jubal’s Raid by Frank E. Vandiver

- Maryland Voices of the Civil War edited by Charles W. Mitchell

- Desperate Engagement by Marc Leepson

- Scraping the Barrel: The Military Use of Substandard Manpower, 1860-1960 edited by Sanders Marble

- Union Soldiers and the Northern Home Front edited by Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller

- After Chancellorsville: Letters from the Heart edited by Judith A. Bailey & Robert I. Cotton

- Gone for a Soldier: The Civil War Memoirs of Private Alfred Bellard edited by David Herbert Donald (my second favorite from this list)

Although I don’t have the book yet, I’ve gone through Ronald S. Coddington’s website “Faces of the Civil War” several times. Fantastic images and he’s obviously gone through a lot of trouble to get the stories of the men behind the photos.

AND after having a GREAT phone conversation with Susan Claffey who is a past president of the Civil War Roundtable of the District of Columbia, I have a new book for my list: As I Remember: A Civil War Veteran Reflects on the War and Its Aftermath by Lewis Cass White and edited by Joseph Scopin.

I also have to give a shout-out to the National Park Service who has a wonderful brochure on the Battle of Fort Stevens.

Washington’s #CivilWar Forts and Parks – Video

Before beginning this project, I had never heard of the Fort Circle Parks. It is a 37-mile-long arrangement of fortifications that encircle the capital. They consist of 68 forts, 20 miles of rifle pits, and are connected by 32 miles of roads. Fort Stevens is one of those forts, built to defend the main approach to Washington from the north – 7th Street Pike (now Georgia Avenue).

Before beginning this project, I had never heard of the Fort Circle Parks. It is a 37-mile-long arrangement of fortifications that encircle the capital. They consist of 68 forts, 20 miles of rifle pits, and are connected by 32 miles of roads. Fort Stevens is one of those forts, built to defend the main approach to Washington from the north – 7th Street Pike (now Georgia Avenue).

In the 1900s, there was a plan to buy up land connecting all of the forts and create a green ring of parks and trails around Washington DC. Although not fully realized, there were some efforts made (and continue to be made) to realize the McMillan Plan. Today, nineteen of the fort sites are administered by the National Park Service, while four are administered by other local and state governments.

The video below is from a fantastic panel at the National Archives from 2014:

During the Civil War, the Union army constructed a series of earthen defenses in and around Washington to protect the nation’s capital from attack. The defeat of Confederate forces at one of these―Fort Stevens―helped keep Washington in Union control. Dr. B. Franklin Cooling, historian, author, and Professor of History, National Defense University, and Loretta Neumann, Vice President, Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington, will discuss the development of Washington’s Civil War forts, their role in the war, and their ensuing transformation into the public parks and cultural resources known as the Fort Circle Parks. This program is presented in partnership with the National Capital Planning Commission and will function as the kick-off for the official commemoration of the 150th anniversary of The Battle of Fort Stevens.

For more information check out the Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington.

#Disabilities in the Invalid Corps

When talking about the Invalid Corps one of the first questions that usually arises is who were these men? What kind of disabilities did they have? The question is answered (in detail) in General Orders, No. 212 from the War Department, Adjutant-General’s Office (July 9, 1863):

When talking about the Invalid Corps one of the first questions that usually arises is who were these men? What kind of disabilities did they have? The question is answered (in detail) in General Orders, No. 212 from the War Department, Adjutant-General’s Office (July 9, 1863):

In executing the provisions of General Orders, No. 105, from this Department, in regard to the selection of men for the Invalid Corps, Medical Inspectors, Surgeons in charge of Hospitals, Camps, Regiments, or of Boards of Enrollment, Military Commanders, and all others required to make the physical examination of men for the Invalid Corps, will be governed in their decisions by the following list of qualification and disqualifications for admission into this Corps:

Physical infirmities that incapacitate Enlisted Men for Field Service, but do not disqualify them for service in the Invalid Corps.

1. Epilepsy, if the seizures do not occur more frequently than once a month, and have not impaired the mental faculties.

2. Paralysis, if confined to one upper extremity.

3. Hypertrophy of the heart, unaccompanied with valvular lesion. Confirmed nervous debility or excitability of the heart, with palpitation, great frequency of the pulse, and loss of strength.

4. Impeded respiration following injuries of the chest, pneumonia, or pleurisy. Incipient consumption.

5. Chronic dyspepsia or chronic diarrhoea, which has long resisted treatment. Simple enlargement of the liver or spleen, with tender or tumid abdomen

6. Chronic disorders of the kidneys or bladder, without manifest organic disease, and which have not yielded to treatment. Incontinence of urine; mere frequency of micturition does not exempt.

7. Decided feebleness of constitution, whether natural or acquired. Soldiers over fifty, and under eighteen years of age, are proper subjects for the Invalid Corps.

8. Chronic rheumatism, if manifested by positive cl???ge of structure, wasting or contraction of the muscles of the affected limb, or puffness or distortion of the joints.

9. Pain, if accompanied with manifest derangement of the general health, wasting of a limb, or other positive sign of disease.

10. Loss of sight of right eye ??? partial loss of sight of both eyes, or permanent diseases of either eye, affecting the integrity or use of the other eye, vision being impaired to such a degree clearly to incapacitate for field service. Loss of sight of left eye, or incurable diseases or imperfections of that eye, not affecting the use of the right eye, nor requiring medical treatment, do not disqualify for field service.

11. Myopia, if very decided or depending upon structural change of the eye. Hemeralopia, if confirmed.

12. Purulent otorrhoea; partial deafness, if in a degree sufficient to prevent hearing words of command as usually given.

13. Stammering, unless excessive and confirmed.

14. Chronic aphonia, which has long resisted treatment, the voice remaining too feeble to give an order or an alarm, but yet sufficiently distinct for intelligible conversation.

15. Incurable deformities of either jaw, sufficient to impede but not to prevent mastication or deglutition. Loss of a sufficient number of teeth to prevent proper mastication of food.

16. Torticollis, if of long standing and well marked.

17. Hernia; abdomen grossly protuberant; excessive obesity.

18. Internal hemorrhoids. Fistula in ???no, if extensive or complicated, with visceral disease. Prolapsus ani.

19. Stricture of the uretha.

20. Loss or complete atrophy of both testicles from any cause: permanent retraction of one or both testicle with in the inguinal canal.

21. Varicocele and cirsocele, if excessive, or painful; simple sarcocele, if not excessive nor painful.

22. Loss of arm, forearm, hand, thigh, leg or foot.

23. Wounds or injuries of the head, neck, chest, abdomen or back, that have impaired the health, strength or efficiency of the soldier.

24. Wounds, fractures, injuries, tumors, atrophy of a limb or chronic diseases of the joints or bones, that would impede marching, or prevent continuous muscular exertion.

25. Anchylosis of the shoulder, elbow, wrist, knee or ankle joint.

26. Irreducible dislocation of the shoulder, elbow, wrist or ankle joint, in which the bones have accommodated themselves to their new relations.

27. Muscular or cutaneous contractions from wounds or burns, in a degree sufficient to prevent useful motion of a limb.

28. Total loss of a thumb, loss of ungual phalanx of right thumb; permanent contraction or extension of either thumb.

29. Total loss of any two fingers of the same hand.

30. Total loss of index finger of right hand; loss of second and third phalanges of index finger of right hand, if the stump is tender or the motion of the first phalanx is impaired. Loss of the third phalanx does not incapacitate for field-service.

31. Loss of the second and third phalanges of all the fingers of either hand.

32. Permanent extension or permanent contraction of any finger, except the little finger: all the fingers adherent or united.

33. Total loss of either great toe; loss of any three toes on the same foot; all the toes joined together.

34. Deformities of the toes, if sufficient to prevent marching.

35. Large, flat, ill-shaped feet, that do not come within the designation of talipes valgus, but are sufficiently malformed to prevent marching.

36. Varicose veins of interior extremities, if large and numerous, having clusters of knots, and accompanied with chronic swellings.

37. Extensive, deep and adherent cicatrices of lower extremities.

An Invalid Corps Song?

In 1862, General Order No. 105, of the U.S. War Department created the Invalid Corps. A year later, its name was changed to the Veteran Reserve Corps. This popular song written by Frank Wilder gives a good idea of what the sentiment was towards these men at the time. The song tells the story of a young man who tried to join the Union army but was rejected because of his various ailments. The rest of the song basically makes fun of the invalid corps and the men who were exempted from front line duty. One wonders how much it had to do with the eventual name change.

In 1862, General Order No. 105, of the U.S. War Department created the Invalid Corps. A year later, its name was changed to the Veteran Reserve Corps. This popular song written by Frank Wilder gives a good idea of what the sentiment was towards these men at the time. The song tells the story of a young man who tried to join the Union army but was rejected because of his various ailments. The rest of the song basically makes fun of the invalid corps and the men who were exempted from front line duty. One wonders how much it had to do with the eventual name change.